St. Mullins is a unique place. Within its confines are daily reminders of the physical remains of most of the defining periods and the great events of Irish history, from early Christianity up to the present day.

We have the monastic settlement, the holy well, Viking place names, the Norman motte and bailey, and the historic graveyard with distinctive 18th century ornamented headstones enclosing a Penal Altar and graves from the Battle of the Boyne and Battle of Aughrim, of Kavanagh Kings of Leinster, and of local 1798 rebels.

There is also the 18th century industrial heritage of the river canal and corn, tuck and woollen milling. The memory of lives past, of traditional craft and culture still resonate through an active folklore and oral tradition.

Early History

The early history of St. Mullins is shrouded in myths and legends. It is recorded in the Book of Leinster that in the third century, four hundred years before St. Moling built his monastery at St. Mullins, Beasal Bealach (the then King of Leinster), engaged the mythical warrior Finn McCool and his army, the Fianna, to help him defeat the High King Cairbre Lifechair, who had marched into Leinster to enforce the dreaded Bóroma Tax, which was paid in cows.

Beasal won the battle at Camross, where nine thousand were killed, but later Cairbre defeated him in the Battle of Dubchomar, and from then on exacted the Bóroma Tax.

Indeed, there are many accounts of Fionn and the Fianna taking part in battles near St. Mullins.

St. Moling 614 – 696

In the Bergundian Library in Brussels, there is a manuscript entitled “The Birth and Life of St. Moling” copied in 1628 by Micheál Ó Cléirigh (one of the Four Masters) from an older manuscript “The Book of Tighe Mulling”, which cannot now be found. It begins by describing how St. Brendan, The Navigator, sailed up the River Barrow to what is now St. Mullins with the intention of setting up a monastic community there. But an angel appeared to him and told him that thirty years hence, Moling of Linn Mór would come to build his monastery at Ros Bruic (Badger’s Wood), the old name for St. Mullins. Brandon Hill on the west bank of the River Barrow gets its name from St. Brendan.

St. Moling was born in the Sliabh Luachra area of Co. Kerry, near the village of Brosna, in 614. Both he and his mother were taken into the protection of St. Brendan’s Monastery at Uaimh Brennáinn, where Moling was first educated by Collannach, a great teacher of that time.

St. Moling was born in the Sliabh Luachra area of Co. Kerry, near the village of Brosna, in 614. Both he and his mother were taken into the protection of St. Brendan’s Monastery at Uaimh Brennáinn, where Moling was first educated by Collannach, a great teacher of that time.

When Moling had reached maturity, Collannach cut the monk’s tonsure on his head and he started out as a priest. He first visited St. Modimoc at Cluain Cain (Clonkeen, Co. Tipperary), where he entered into a covenant with the community. He continued on to Cashel, where the King of Munster offered him a site for an abbey church. However, that night an angel reproached him for having asked for it when there was already a place ready for him on the stream pools of the Barrow, where St. Brendan the Navigator had thirty years before had made a hearth, and the fire was still kept burning.

From this he proceeded to Sruthair Guaire (Shrule in Co. Laois) and from there to complete his studies under St. Aidan of Ferns (Mo Aeodh Óg). It was under his patronage that Moling came to Ros Bruc (Badger’s Wood), the old name for St. Mullins by the stream pools of the Barrow.

Here he built his church and living accommodation for his monks, and being a practical man, his next priority was a mill to grind corn to feed his monastery and local people. A man of great physical strength and energy, he is renowned for cutting single-handedly a mill race a mile long (which can still be traced) to power his mill, which took seven years. He refused to wash or drink from it until it was completed.

He started the first ferry service across the Barrow in his home-made raft – a service that survived to the 1960s. He will always be remembered for the remission of the Bóromean Tribute, an oppressive tax paid in cows, levied on the people of Leinster for many years by the High Kings of Ireland. This was regarded as a great feat by the Leinster men who greatly honoured Moling for it.

He became Bishop of Ferns and Glendalough and was made Archbishop of Ferns and successor to St. Aidan in 691. He died at St. Mullins in 696 and his relics were held in Temple Mór until they were destroyed in the great fire of 1138.

The Pilgrim’s Way

Because of the many miracles performed by St. Moling during his life and those attributed to him after his death, St. Mullins became a place of pilgrimage, a form of which survives today.

There were at least four different phases of the pilgrimage as it became modified and adapted to suit the changes from Celtic monasticism to the coming of the Normans, and the restrictions imposed by the Penal Laws and current religious practices. Despite all the changes down through the ages, the actual Pilgrim’s Way route has remained largely the same.

The Start of the Pilgrimage

When St. Moling completed his mill race, he assembled all the local dignitaries, chieftains and clerics for its blessing and that of the corn mill. This was on July 25th, The Feast of St. James, Patron Saint of Pilgrims. The “Life of Moling” describes how a large crowd came from all over the countryside for the blessing. Moling led the proceedings “by wading against the flow of the water to the place where it diverted from the river and praying for all who came to this place of pilgrimage, in commemoration of the event, would find healing of body and spirit”. This is how St. Mullins’s became a place of pilgrimage which continues today.

The Black Death

This Pilgrimage is well documented in the “Annals of the Four Masters”, where the Franciscan Friar, John Clynn from Kilkenny, describes at the time of the Black Death in 1348, how noblemen and peasant, rich and poor, queued up in Cluin Thurris, “The Meadow of the Pilgrims”, beside the present car park near the Blessed Well. At that time people didn’t realise that flea bites from infected rats was causing the plague, and by immersing themselves in the Blessed Well, they were actually doing the right thing. However, Friar Clynn did not get cured after his pilgrimage to St. Mullins, and he passed away later that year from the plague.

The Viking Era

The monastery at St. Mullins prospered and became a target for a large fleet of Vikings who landed in Waterford in 824/825 and sailed up the Barrow and plundered St. Mullins. Again, in 951 the monastery was plundered by Vikings led by Láiric, after whom Port Láirge (Waterford) got its name. Some Vikings settled in St. Mullins. Fragments of Viking pottery were found when building the boatslip at St. Mullins in the 1990’s.

The Norman Years

The Anglo-Norman invasion, led by Richard de Clare (Strongbow), took place in 1169. They were attracted to St. Mullins by the presence of a thriving monastic site and Viking settlement.

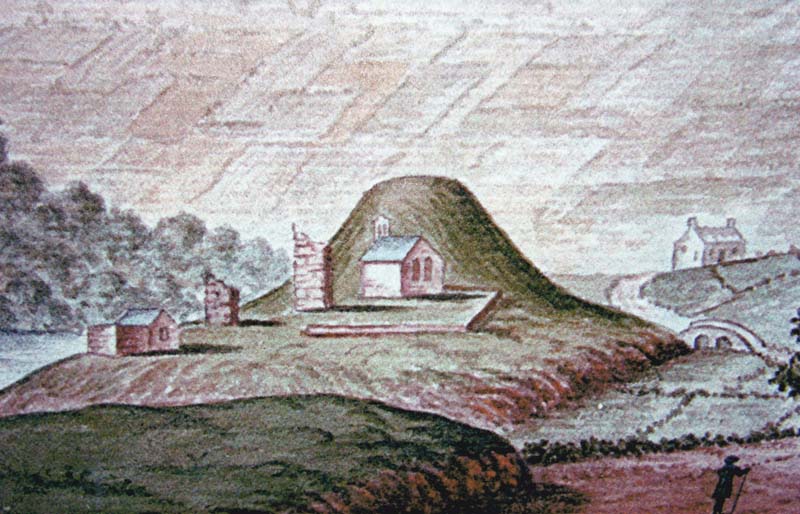

By 1171, a manor house was established with a typical motte and bailey castle. This for a time was in the possession of Raymond le Gros before it passed to his heirs, the Carews.

The motte was a flat-topped mound of earth which was surrounded by a ditch or fosse and fortified with a palisade fence with a tall watch tower on top. It was built to dominate passage and the crossing on the river Barrow, which is tidal to St. Mullins.

Attached at one side was a rectangular bailey or banked enclosure which would have housed the castle’s garrison and household.

Attached at one side was a rectangular bailey or banked enclosure which would have housed the castle’s garrison and household.

Around 1300, Richard Tallon, then Lord of the Manor, granted the monastic site to the Cistercian Abbey of Tintern, Co. Wexford. In 1323, Edmund Butler killed Philip Tallon, his son and others, and burned the church with men, women and children who had sought refuge there. The relics of St. Moling were also destroyed. In 1347 the town of St. Mullins was rebuilt by Walter Birmingham.

Some years after the dissolution of the monasteries in 1540, St. Mullins with its barony was granted to the Colclough family as part of the possessions of Tintern Abbey. However, Brian McCahir McArte Kavanagh managed to retain the barony of St. Mullins, which had been granted to his father in 1539, on condition that he built a mansion house there and inhabited it in order to control the harassment of the settlers by the native Irish.

In 1581 Anthony Colclough was contracted to erect a robust fort at St. Mullins to hold a government garrison which was maintained in the star-shaped fort on Coolyhune Hill until 1634. The fairly-well preserved fort is still there today.

The Blessed Well

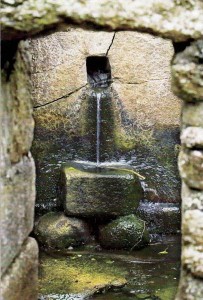

The Blessed Well consists of a stone reservoir and a small oratory into which the water flows through two cut stone square openings in the wall. The water flows down to the rough flagstone floor and flows out through the doorway. The projection of the side walls beyond the gable is typical of early Celtic Christian architecture.

Recent research by Dr. Tomás O Carragáin, UCC, indicates that it is the remains of a baptismal chapel built over “the flowing waters of a holy well, making it the only surviving early medieval well-chapel in Ireland.”

The first reference to a holy well at St. Mullins is to be found in the Annals of Friar Clyn (1348). In those times, the plague swept across Ireland and pilgrims visited the holy well in St. Mullins out of fear of the plague.

The first reference to a holy well at St. Mullins is to be found in the Annals of Friar Clyn (1348). In those times, the plague swept across Ireland and pilgrims visited the holy well in St. Mullins out of fear of the plague.

They would circle the well in a clockwise direction, known as circumambulation, while reciting prayers. This practice goes back hundreds of years. They drank from the well and carried water home for those unable to visit.

The pilgrims made the rounds (a prescribed walk) three times and waded barefoot through the stream. They recited prayers at each of the ruined churches where they prayed nine Our Fathers and nine Hail Marys. In the 1800’s there are accounts of large crowds assembling there on June 17th and July 25th every year.

…To be continued.